The last thing Walt Odegaard wanted to be called was Mr. Odegaard. Not because he denied authority or because he thought Odegaard was two syllables too long, he just wanted to connect with the troubled kids he spent the majority of his life helping.

Walt’s heart was bigger than his 5’11 frame and his attitude off the field seemed to surprise people who saw him power through offensive lineman on his way to All-American honors while at NDSU. His accomplishments will forever be enshrined in the Bison Hall of Fame, but the impact on every life he encountered would mean something much greater than a plaque on the wall.

As irony would have it, one of the most punishing players on the 1965 national championship team that delivered NDSU its first title in school history was described to be “as gentle as a teddy bear” by one of the first employees.

Walt was a big man for his generation, but his dream was even bigger: establish his own getaway for underprivileged youth in the state. That heart molded him into a football star.

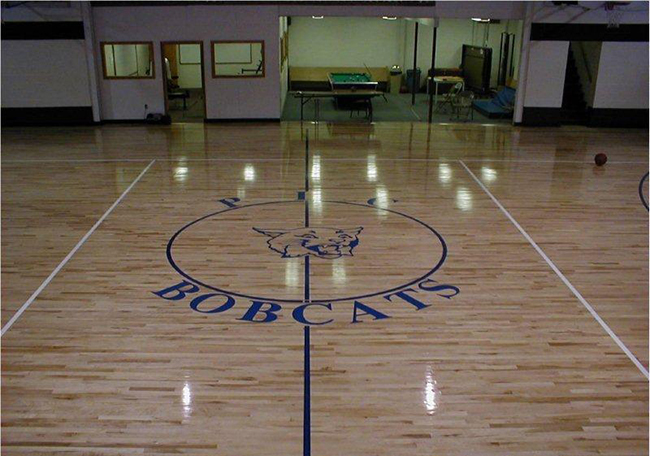

The Prairie Learning Center was created with the premise of being a youth sanctuary: a safe place where kids, dealt with the life equivalent of a two and seven off-suit in poker, can learn in a controlled environment. These kids don’t have much. A drug addict mother or a deadbeat father, maybe both of their parents are together if they’re lucky enough. The bottom line, most of the 40 kids housed at PLC arrive with a one-way ticket to a life of crime and hardship.

But Walt had a different attitude and a plan. This wasn’t going to be the place he previously worked at when he supervised at Thistledew Camp in Togo, Minn., or the Youth Corrections Center in Mandan, N.D. He saw potential behind the trouble faced kids, and that vision led him to create PLC with one of his former colleagues at Thistledew and closest friends, Dennis Hanson.

Located 261 miles away from the east entrance of the Fargodome off a dusty dirt road just west of Highway 31, PLC is where Odegaard’s convictions were practiced daily.

PLC houses up to 40 boys at a time with no prison bars and locked cells. Its strength is its mission of rehabilitation. The boys choose to go and stay for an average of six months and are educated and given a proper chance at a real future in the real world.

“We try to have them get back on the right track so they can become good citizens and make a living for themselves,” explains office manager Leona Koch. She’s the only remaining employee at PLC since Walt and Hanson opened its doors. Koch says she still remembers when her church group was first introduced to Walt’s vision 25 years ago.

Walt and Hanson were looking for a spot for their youth camp and that’s when they stumbled into Raleigh, N.D., through an old connection at the YCC. Father Joe Deichert was the chaplain there and brought the men 60 miles south to check out an abandoned private high school. The hallways and classrooms of St. Gertrude High School were to become the location of Walt’s big dream.

PLC opened its doors on Sept. 11, 1991, after receiving its license through the state’s human service office.

Once the asepsis was removed and renovation was complete, beds started filling up at PLC, said Koch. Soon eight beds weren’t enough, and as soon as they reached 16, they were applying for a license for 32. Suddenly, the number reached 50.

Walt was the facility administrator until his retirement in 1994.

“He was connected,” Koch said. “His motto was: walk and talk with the boys. He wanted to make sure that they felt needed. They felt they were important and that was just his method of helping them.”

Dave Marion took over the administrative position as the executive director at PLC in 1998, something that never would have happened if Walt didn’t offer Marion a position on the PLC team after his decorated career on the football field at NDSU.

Marion grew up the son of a chief parole officer in Bismarck and was well aware of the other side of the justice system when hope was lost in preventing criminal behavior. He knew he needed to help the youth if he wanted to make an impact. That’s why he jumped at the opportunity to join Walt and the staff at PLC in 1992.

“He never lied and there was something in Walt’s delivery,” the former Bison offensive lineman, Marion, said. “Talking about how he was going to help kids. How he was going to help families in the state of North Dakota and some missing links within our systems.”

“I say he was my mentor at the beginning,” Koch said. “He tried to be the father figure for awhile that the kids didn’t have before they came in.”

Koch says the culture hasn’t changed since Walt’s departure and his death in 2006, five days after PLC’s 15th birthday.

Maybe the key is its rural-ness. Both Koch and Marion seem to agree that with no locks on the doors (state mandate), nature acts as the gates. The environment is an important piece of bringing the boys together and it allows time for the staff to connect with them on a personal basis.

Hanson, or “Pops” as the boys used to call him, loved taking the boys cross- country skiing and snowshoeing, said Koch. They became a sort of family, the sort that boys never had a real chance of attaining since entering this world.

“They acted like they were the meanest kids in the world,” Koch said about most of the boys that arrive. “But if somebody would get hurt, they would be right there.”

Koch tells the story of the second boy they had at the camp. He saw Pops fall from a ladder and quickly went to his aid before running to find help. She also mentions the time one of the boys found an elderly laundry lady on the ground in the laundry room who had apparently had a fainting spell while on the job.

At PLC, these kids were given the chance to be normal. It was a chance to be intertwined with real life and get out of the poor and toxic environment they grew up absorbing.

Pops has moved on from PLC and is now living in Sandstone, Minn., with his wife. He still makes an annual visit during an open house and sometimes during deer hunting season.

Walt has been gone for nearly 10 years now, but his presence is still felt through the care of every employee at PLC, especially his protégé and fellow Bison football player, Marion.

“At the end of the day, I know what we’re creating down there. We make a huge impact with kids and families,” said Marion. “I can go to sleep at night. It’s not that I don’t worry about stuff, but I know that we’ve given our best. We got our people that we need in place that are going to deliver their best day in and day out. We make a huge impact.”

We talk a lot about Bison Pride and the importance of the herd is what an individual does that’s best for the herd, usually shown through a selfless decision. PLC mirrors that sentiment: Be driven, and do what’s best for the community, to not only strengthen yourself but to strengthen the culture. And the culture at PLC can be read on the wall: “Every child has an opportunity to succeed.”

And at PLC, that opportunity Walt dreamt about is becoming a reality for the boys every day.